https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/05/business/fiat-chrysler-renault-merger-withdrawal/index.html

2019-06-06 08:14:00Z

CAIiENuVUp_aFgo4t9IwitzOO8cqGQgEKhAIACoHCAowocv1CjCSptoCMPrTpgU

- Chris Isidore and Sherisse Pham contributed to this report

Workers transport soil containing rare earth elements for export at a port in Lianyungang, Jiangsu province, China October 31, 2010.

Stringer | Reuters

European manufacturers will need to keep an eye on China's "near-monopoly" on the extraction and supply of rare earth minerals as they move toward electric power, experts have told CNBC.

Rare earths — minerals found in a wide range of everyday consumer electronics — hit the headlines over the past week as China hinted at stopping the export of rare earths to the U.S., after Washington increased tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods.

The group of 17 minerals aren't actually rare, but are produced in fairly scarce quantities compared with abundantly mined metals like copper. They have grown in prominence in recent years due to their use in high-tech equipment, defense manufacturing and electric vehicles.

China extracted 70% of the world's rare earths in 2018.

Martin Eales, CEO of London-listed Rainbow Rare Earths, which runs an ongoing mining project in Burundi, told CNBC that China may not opt for an outright export ban but rather a reduction in its production quota, which "by definition would reduce the amount of rare earths material available for export and potentially create supply problems for rest-of-the-world users."

The automotive revolution

The long-term concern for European manufacturers, however, will be the increased volume of rare earths required, according to the British Geological Survey's Science Director for Minerals, Andrew Bloodworth.

As the automotive sector moves from internal combustion engines to electric vehicles, many of those electric motors will rely on high field strength electric magnets which contain rare earth components.

"This isn't going to happen overnight, but as the automotive sector moves from petrol and diesel power to electric, you can make a very efficient small powerful electric motor using high field strength magnets," Bloodworth told CNBC.

"The difference there is just that the volumes required to manufacture the millions and millions of cars every year are going to change the game, because they're going to up that demand for materials."

Vertical integration

Bloodworth suggested that the Chinese are aware of the changing portfolio of materials required by the auto industry, adding that they are "particularly interested in selling the global automotive sector motors or even finished cars rather than rare earths."

"So we may see the market operating in a sense that if this demand does ramp up quickly, prices will rise, therefore some of these projects which are kicking around in the rest of the world will come to pass because they will become more attractive to investors," he said.

At the moment, non-Chinese mines are a difficult proposition for investors owing to the scale of Chinese dominance, but Bloodworth suggested any imposition of tariffs or restrictions would be "nuanced," as it would not be in Chinese interests to hike prices in a way that encourages alternative supply sources to enter the market.

Eales agreed that an added interest for companies like Rainbow, operating non-Chinese mines, is "speculation as to how it may fit into a future supply chain that attempts to bypass China entirely."

"There is going to be so much demand from the vehicle market for rare earths that some of these projects will come to pass anyway," said Bloodworth.

"They may be acquired by Volkswagen or Toyota for instance — they will be buying supply and vertically integrating. "

He suggested that Europe was becoming more concerned about the raw material supply chain, owing to its role as a major producer of finished vehicles and the threat that Chinese monopolization of the supply chain poses.

The British Geological Survey has been communicating to the British government the importance of understanding this shifting tide for global manufacturing.

Sen. Bernie Sanders took his crusade against Walmart to the mammoth retailer's annual meeting Wednesday, backing a push to give workers a spot on the company board.

The Vermont independent stopped in Bentonville, Arkansas, in the heat of the 2020 Democratic presidential primary to show support for Walmart's hourly associates. Sanders — who has long pushed the retailer to boost wages and benefits — sees condemnation of corporate titans as a way to separate himself from a crowded Democratic field.

The senator introduced a shareholder proposal — on behalf of Walmart employee and labor advocate Cat Davis — that would make the company's roughly 1.5 million hourly workers eligible for board nominations. Founder Sam Walton's family holds a majority of the company's shares and opposes the measure.

"Walmart can strike a blow against corporate greed and a grotesque level of income and wealth inequality that exists in our country," Sanders said in a two-minute comment introducing the proposal and calling for wage increases at Walmart.

Results of the shareholder vote were expected later in the day.

Sanders' appearance holds obvious political benefits for the senator. He criticized Walmart's leadership while standing in the same room as its CEO Doug McMillon — and backed the working-class voters he hopes will help propel him to the Democratic presidential nomination.

"Frankly, the American people are sick and tired of subsidizing the greed of some of the largest and most profitable corporations in this country," Sanders added during his remarks, noting that some Walmart employees rely on public assistance programs such as Medicaid.

Protestors gather outside Walmart's shareholder meeting as Sen. Bernie Sanders was slated to speak at the event.

Amanda Lasky | CNBC

Protesters gathered outside the meeting — some from the group "United for Respect," which has pushed for a worker presence on Walmart's board — held signs supporting Sanders' 2020 campaign and calling for a $15 per hour minimum wage.

When Sanders confirmed last month he would attend the meeting, Walmart said it hoped the senator would "approach this visit not as a campaign stop, but as a constructive opportunity to learn about the ways we're working to provide increased economic opportunity, mobility and benefits to our associates."

Before Sanders spoke, McMillon highlighted the company's efforts to increase its starting wage to $11 per hour. He also called on Congress to pass a "thoughtful plan to increase" the federal minimum wage, taking into account "phasing and cost of living increases to avoid unintended consequences."

"It's clear by our actions, and those of other companies, that the federal minimum wage is lagging behind," McMillion said, adding "$7.25 is too low. "

On Wednesday, Sanders argued that a $15 per hour minimum wage "is not a radical idea." He noted that Walmart competitors such as Amazon and Target have started to phase in a $15 per hour pay floor.

As criticism of wealthy individuals and corporations has taken hold across the political spectrum, 2020 Democratic candidates have more directly targeted large corporations. Along with Walmart, Sanders has slammed Amazon and its CEO Jeff Bezos and helped to push the company to hike its minimum wage to $15 per hour.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., has also taken aim at corporate America, pushing to break up tech companies such as Amazon and Apple and agricultural giants such as Monsanto. Warren has proposed a plan to allow employees to select at least 40% of a company's board members.

Sanders and Warren's stances have distanced them from rivals like former Vice President Joe Biden, who has tried not to seem too hostile to corporate America.

During the campaign so far, presidential candidates have showed support for workers on strike at grocery chain Stop & Shop and other companies.

Beauty chain Sephora has closed its US stores for Diversity training, a month after a singer said she had been racially profiled.

RnB star SZA said she had been targeted while shopping at a branch in California.

The firm told Reuters it was aware of the incident but said the training was not "a response to any one event".

The BBC spoke to Asad Dhunna from the Unmistakables, who advises companies on how to be more racially inclusive.

Video journalist: Sophie Van Brugen

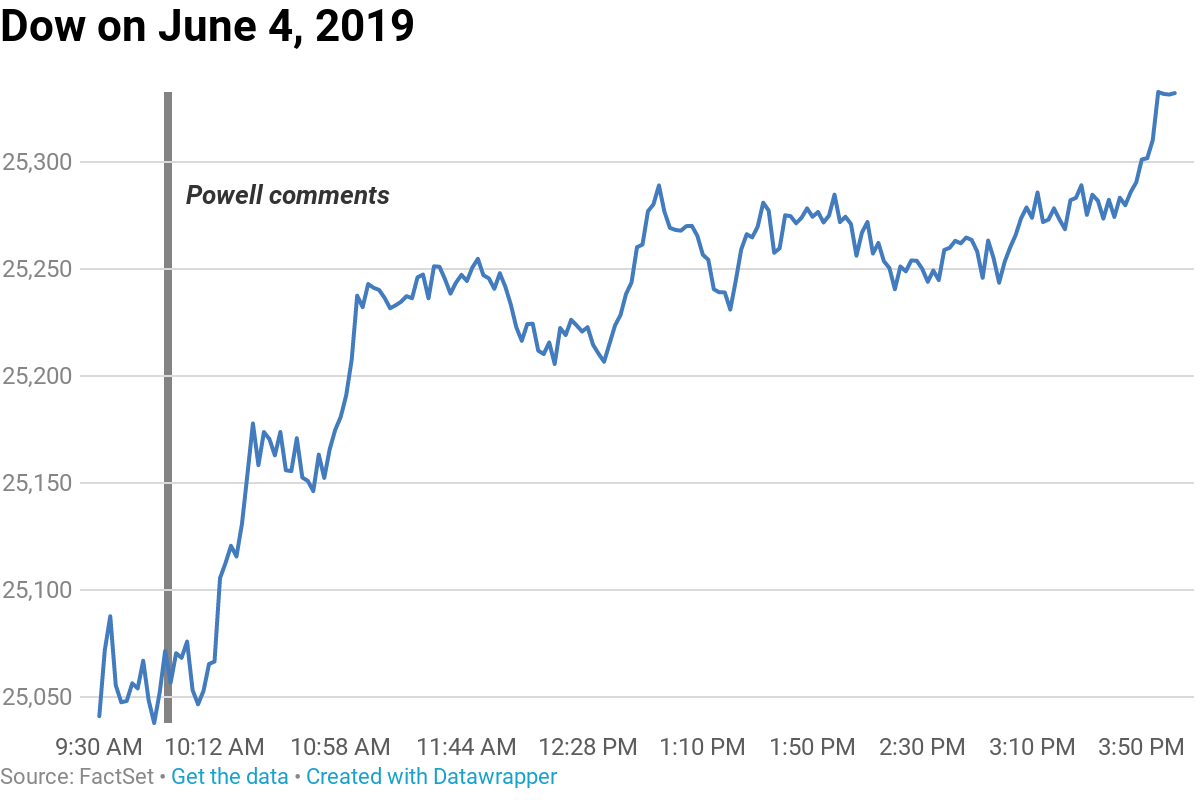

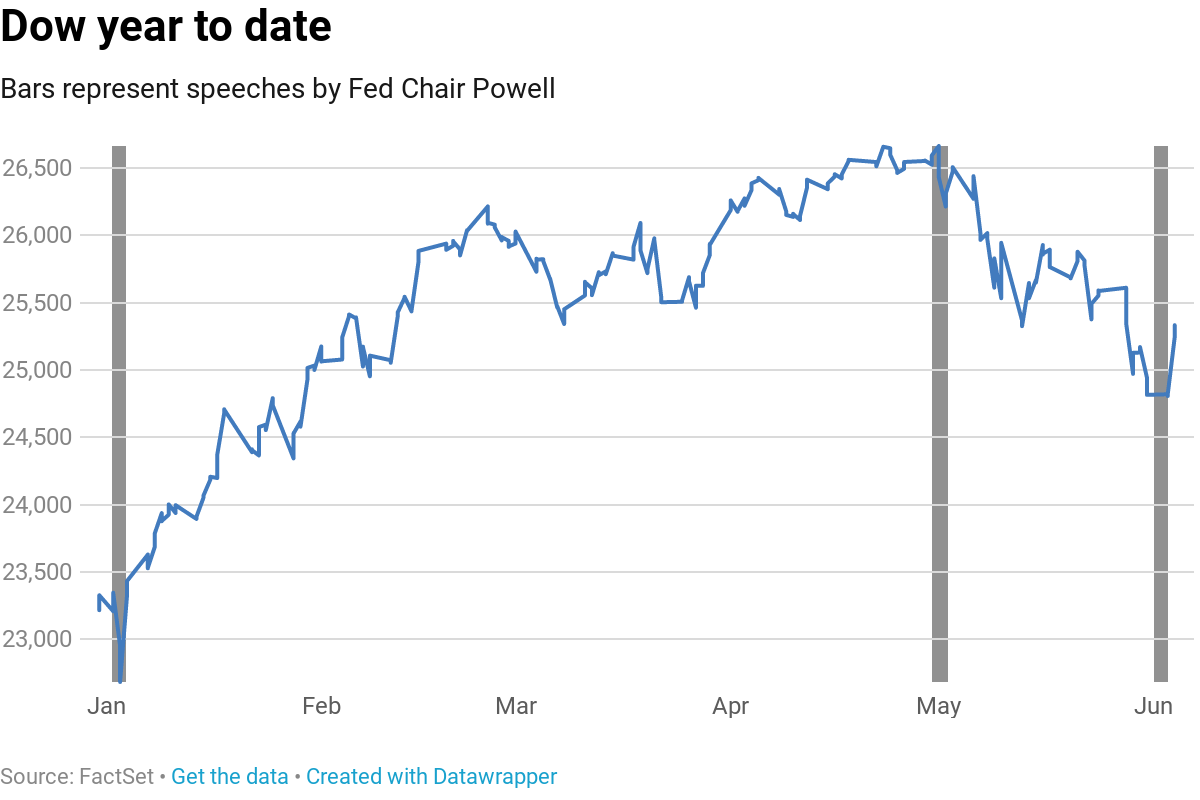

The Dow Jones Industrial Average rallied more than 500 points on Tuesday (and was continuing that rally Wednesday) after Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell opened the door to a rate cut that traders have been crying for because of fears the economy is slowing.

Their love of Powell's pivot is evident in this Dow chart here:

"We will act as appropriate to sustain the expansion," was all Powell said, but that was enough to cause the market to leap.

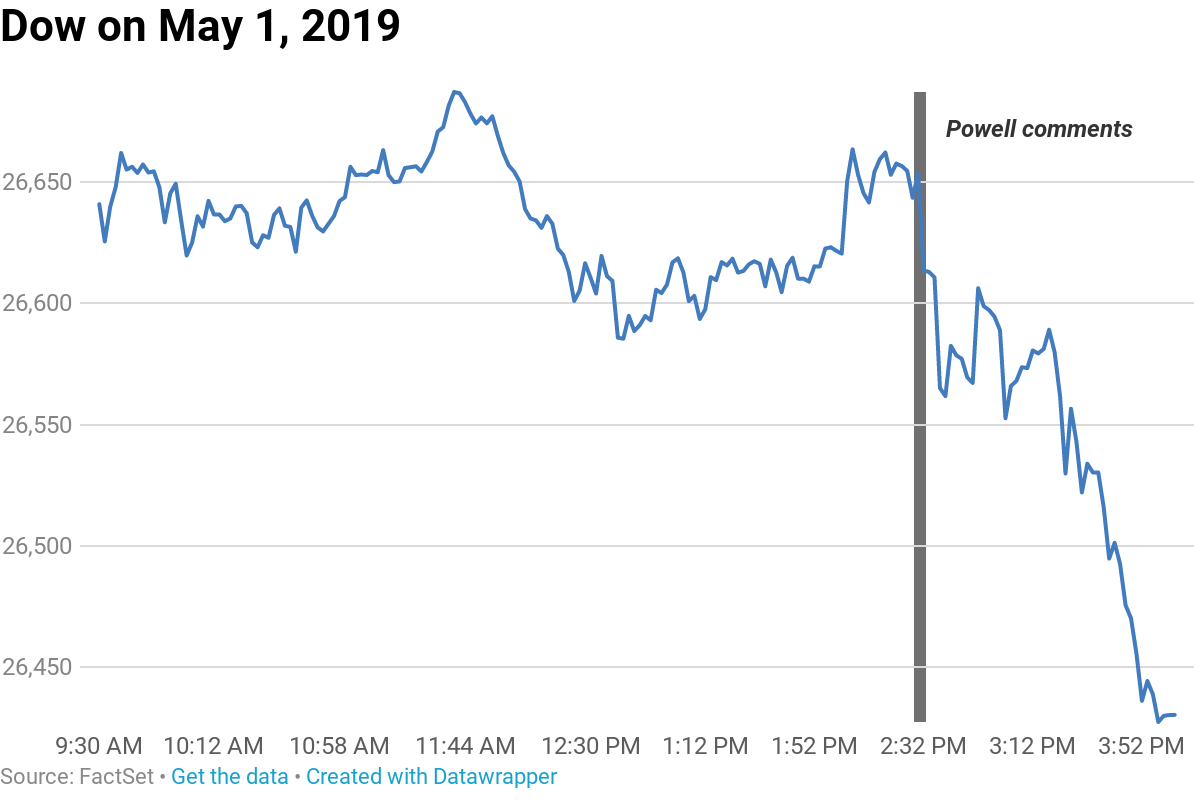

Now contrast that with what happened on May 1, when Powell disappointed investors by appearing to downplay the odds of a rate cut by saying that he believed a slowdown in inflation was likely "transitory."

The Dow shed 150 points during that session.

What a difference a month makes when there's a vicious sell-off in risk assets.

"Powell's assurance the Fed will 'act as appropriate to sustain the expansion' was confirmation that not only is a rate cut on the table, but it is nearing on the horizon," Ian Lyngen, head of U.S. rate strategy at BMO, wrote in an email. "Risk assets improved in the wake of the dovish undertones; at least that aspect of Tuesday's price action fit with our broader understanding of the world."

"A preemptive cut was priced-in, which suggests if the Fed doesn't follow-through it will be risk off," he added.

— CNBC's Jeff Cox contributed reporting.

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders speaks during a 2015 rally to push for a raise to the minimum wage to $15 an hour. Andrew Harnik/AP hide caption

Bernie Sanders may not have his usual adoring crowds at his Wednesday campaign stop. That's because he'll be speaking to Walmart shareholders at their annual meeting.

The Vermont senator and 2020 Democratic presidential candidate will present a proposal aimed at giving workers representation on the company's board, echoing a policy he is reportedly working on. (Elizabeth Warren has released a similar policy.)

On Tuesday afternoon, Sanders released a statement criticizing Walmart for issues beyond worker representation on the board.

"It is time for Walmart to pay all of its workers a living wage, give them a seat at the table, stop blocking them from joining a union and allow part-time employees to work full-time jobs," he said.

It's not just Sanders; this is an example of a tactic that has gained traction in the 2020 presidential race, of candidates calling out specific companies in their campaigning and their policies.

Sanders is presenting the resolution on behalf of Cat Davis, a Walmart worker and shareholder, and a leader of the group United for Respect, which aims to protect workers' rights at large corporations.

The proposal would require that the board include hourly associates on its lists of potential new members. Sanders will have three minutes to present the resolution, and it will be put to a vote on Wednesday. The resolution is not expected to pass.

Candidates vs. corporations

Sanders in 2018 already took aim at Walmart with the Stop WALMART Act — "WALMART" here standing for "Welfare for Any Large Monopoly Amassing Revenue from Taxpayers." That bill would have stopped large employers from undertaking stock buybacks unless they take particular steps to boost workers, like paying them at least $15 an hour.

He's introduced another bill with a pointed acronym, the Stop BEZOS Act (That is, "Stop Bad Employers by Zeroing Out Subsidies") — a title aimed at Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. That bill would tax large employers for the social safety net programs, like food stamps, that their workers use.

Technology firms have also come under scrutiny among candidates, as they are under scrutiny on Capitol Hill. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., in March released a plan to break up big tech companies, with the aim of allowing smaller companies to thrive. In her unveiling, she called out particular companies by name.

"My administration will make big, structural changes to the tech sector to promote more competition — including breaking up Amazon, Facebook, and Google," Warren wrote in a March Medium post. Since then, Sanders and Hawaii Rep. Tulsi Gabbard have voiced support for her plan.

In addition, strikes at the grocery store chain Stop and Shop drew support from candidates including Warren, South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and former Vice President Joe Biden. Similarly, strikes at McDonald's restaurants have drawn support from multiple candidates.

Rising populism on display

Democratic candidates did take aim at corporations in the 2016 campaign — Bernie Sanders took aim at McDonald's for its wages. Both he and Hillary Clinton did join striking Verizon workers in 2016.

"We were always struggling with, 'How do you make policy tangible?'" said Amanda Renteria, political director for the 2016 Clinton campaign. "And that's a really easy way to do so. People know what Walmart is. People have a conception about it."

But Clinton rarely referenced specific companies negatively on the 2016 campaign trail.

"That really wasn't her style," said Renteria.

It's a tactic that relatively few major candidates have made central to their campaigns in recent years. But the willingness to aggressively call out big companies was arguably long in coming.

"I feel like the political moment we're in is really an outgrowth of really the worker militancy that started in 2012, 2013," said Joseph Geevarghese, executive director of Our Revolution, an advocacy group that grew out of Sanders' 2016 presidential run.

He's talking about walkouts among fast food workers and other low-wage workers that took place in those years (at the time, he was at worker-advocacy group Good Jobs Nation).

Those walkouts themselves had a variety of even older potential causes, he added – long-building inequality; a long, slow recovery from the Great Recession; and the subsequent Occupy Movement, for example.

But whatever the path, the culmination is a political atmosphere where anger is a dominant emotion — and something President Trump has modeled, as well as liberal figures.

"We have been in a populist moment over the last six, seven years," Geevarghese said. "I think Occupy, the strike wave, those are all symbols of that. But I also think Donald Trump is a symbol of the populist wave, at least when it comes to his willingness to go after companies like GM, companies like Carrier."

For her part, Renteria credits Sanders and Warren with having popularized tough anti-corporate rhetoric as a campaign strategy. But she also cautions that it might not work for everyone.

"For somebody like Elizabeth Warren, she has been in this space since the beginning of her career, and so for her it's just validating her brand," Renteria said.

That means calling out Amazon or Walmart seems authentic for candidates like Sanders, Warren and Trump. It might not have for a candidate like Hillary Clinton, and could be a stretch for other Democrats running in 2020.

"I think if other candidates were to take a look at this and go, 'Wow, I can do it too. It makes whatever policy I'm working on more concrete,' that could backfire," Renteria said.

In addition, there's the simple possibility that this kind of rhetoric could create powerful corporate enemies for a candidate at a time when unlimited money is pouring into the coffers of superPACs.

But then, an event like the Walmart shareholders' meeting does allow a candidate to have a media moment that an ordinary policy release might not create. And that's particularly important in a field of about two dozen candidates.

Walmart is one of NPR's financial sponsors.

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders speaks during a 2015 rally to push for a raise to the minimum wage to $15 an hour. Andrew Harnik/AP hide caption

Bernie Sanders may not have his usual adoring crowds at his Wednesday campaign stop. That's because he'll be speaking to Walmart shareholders at their annual meeting.

The Vermont senator and 2020 Democratic presidential candidate will present a proposal aimed at giving workers representation on the company's board, echoing a policy he is reportedly working on. (Elizabeth Warren has released a similar policy.)

On Tuesday afternoon, Sanders released a statement criticizing Walmart for issues beyond worker representation on the board.

"It is time for Walmart to pay all of its workers a living wage, give them a seat at the table, stop blocking them from joining a union and allow part-time employees to work full-time jobs," he said.

It's not just Sanders; this is an example of a tactic that has gained traction in the 2020 presidential race, of candidates calling out specific companies in their campaigning and their policies.

Sanders is presenting the resolution on behalf of Cat Davis, a Walmart worker and shareholder, and a leader of the group United for Respect, which aims to protect workers' rights at large corporations.

The proposal would require that the board include hourly associates on its lists of potential new members. Sanders will have three minutes to present the resolution, and it will be put to a vote on Wednesday. The resolution is not expected to pass.

Candidates vs. corporations

Sanders in 2018 already took aim at Walmart with the Stop WALMART Act — "WALMART" here standing for "Welfare for Any Large Monopoly Amassing Revenue from Taxpayers." That bill would have stopped large employers from undertaking stock buybacks unless they take particular steps to boost workers, like paying them at least $15 an hour.

He's introduced another bill with a pointed acronym, the Stop BEZOS Act (That is, "Stop Bad Employers by Zeroing Out Subsidies") — a title aimed at Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. That bill would tax large employers for the social safety net programs, like food stamps, that their workers use.

Technology firms have also come under scrutiny among candidates, as they are under scrutiny on Capitol Hill. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., in March released a plan to break up big tech companies, with the aim of allowing smaller companies to thrive. In her unveiling, she called out particular companies by name.

"My administration will make big, structural changes to the tech sector to promote more competition — including breaking up Amazon, Facebook, and Google," Warren wrote in a March Medium post. Since then, Sanders and Hawaii Rep. Tulsi Gabbard have voiced support for her plan.

In addition, strikes at the grocery store chain Stop and Shop drew support from candidates including Warren, South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar and former Vice President Joe Biden. Similarly, strikes at McDonald's restaurants have drawn support from multiple candidates.

Rising populism on display

Democratic candidates did take aim at corporations in the 2016 campaign — Bernie Sanders took aim at McDonald's for its wages. Both he and Hillary Clinton did join striking Verizon workers in 2016.

"We were always struggling with, 'How do you make policy tangible?'" said Amanda Renteria, political director for the 2016 Clinton campaign. "And that's a really easy way to do so. People know what Walmart is. People have a conception about it."

But Clinton rarely referenced specific companies negatively on the 2016 campaign trail.

"That really wasn't her style," said Renteria.

It's a tactic that relatively few major candidates have made central to their campaigns in recent years. But the willingness to aggressively call out big companies was arguably long in coming.

"I feel like the political moment we're in is really an outgrowth of really the worker militancy that started in 2012, 2013," said Joseph Geevarghese, executive director of Our Revolution, an advocacy group that grew out of Sanders' 2016 presidential run.

He's talking about walkouts among fast food workers and other low-wage workers that took place in those years (at the time, he was at worker-advocacy group Good Jobs Nation).

Those walkouts themselves had a variety of even older potential causes, he added – long-building inequality; a long, slow recovery from the Great Recession; and the subsequent Occupy Movement, for example.

But whatever the path, the culmination is a political atmosphere where anger is a dominant emotion — and something President Trump has modeled, as well as liberal figures.

"We have been in a populist moment over the last six, seven years," Geevarghese said. "I think Occupy, the strike wave, those are all symbols of that. But I also think Donald Trump is a symbol of the populist wave, at least when it comes to his willingness to go after companies like GM, companies like Carrier."

For her part, Renteria credits Sanders and Warren with having popularized tough anti-corporate rhetoric as a campaign strategy. But she also cautions that it might not work for everyone.

"For somebody like Elizabeth Warren, she has been in this space since the beginning of her career, and so for her it's just validating her brand," Renteria said.

That means calling out Amazon or Walmart seems authentic for candidates like Sanders, Warren and Trump. It might not have for a candidate like Hillary Clinton, and could be a stretch for other Democrats running in 2020.

"I think if other candidates were to take a look at this and go, 'Wow, I can do it too. It makes whatever policy I'm working on more concrete,' that could backfire," Renteria said.

In addition, there's the simple possibility that this kind of rhetoric could create powerful corporate enemies for a candidate at a time when unlimited money is pouring into the coffers of superPACs.

But then, an event like the Walmart shareholders' meeting does allow a candidate to have a media moment that an ordinary policy release might not create. And that's particularly important in a field of about two dozen candidates.

Walmart is one of NPR's financial sponsors.